Vaccines cause autism. Fluoride in our water is responsible for IQ loss. Black people’s immune systems are “better than ours.” COVID-19 is designed to target white people, and those who are Jewish or Chinese are most resistant to the virus.

U.S. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has made many incorrect claims like these throughout his career, all of which have been thoroughly debunked by the scientific community. While the lies Kennedy spouts are terrifying, one specific topic of debate makes my blood boil: the “dangers” of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) medications.

Amid claims that prescribed stimulants are poisoning the nation’s children, students like myself — addicts, in the words of RFK and his ilk — are left to wait and pray that the medicine we depend on won’t be taken away. But it isn’t just the Trump administration perpetuating these harmful ideas. Misinformation is everywhere, and, frankly, I’m tired of it.

Let’s rewind a month or so. Looking at my phone, I noticed that a YouTube channel I’m relatively fond of — Kurzgesagt — uploaded a video about amphetamines, the class of drugs my ADHD medication belongs to. The educational content the channel produces has been a staple of science classrooms for many years, and the information presented is consistently unbiased and well-cited.

Imagine my surprise when the video was of offensively poor quality. Not only was ADHD mischaracterized as a simple tendency to be easily distracted and apathetic, but the video made no distinction between the effects of amphetamine abuse and those of amphetamine medication.

The problem here may not be immediately evident. If the drugs cause the average brain to be “supercharged” and euphoric, surely it’s the same for people with ADHD. Obviously, stimulant medications like Vyvanse and Adderall are just making people high enough to do the stuff they hate. Right?

Wrong.

“I don’t crave the so-called ‘high’ that comes with that focus,” junior Ada Mollo said. “It’s more of a medical necessity…I don’t wake up on the weekends and say, ‘Oh, I really want my medication.’”

I can’t recall how many times I’ve had someone tell me that the Vyvanse I am prescribed is “basically meth.” These widespread misconceptions aren’t just silly; they’re dangerous.

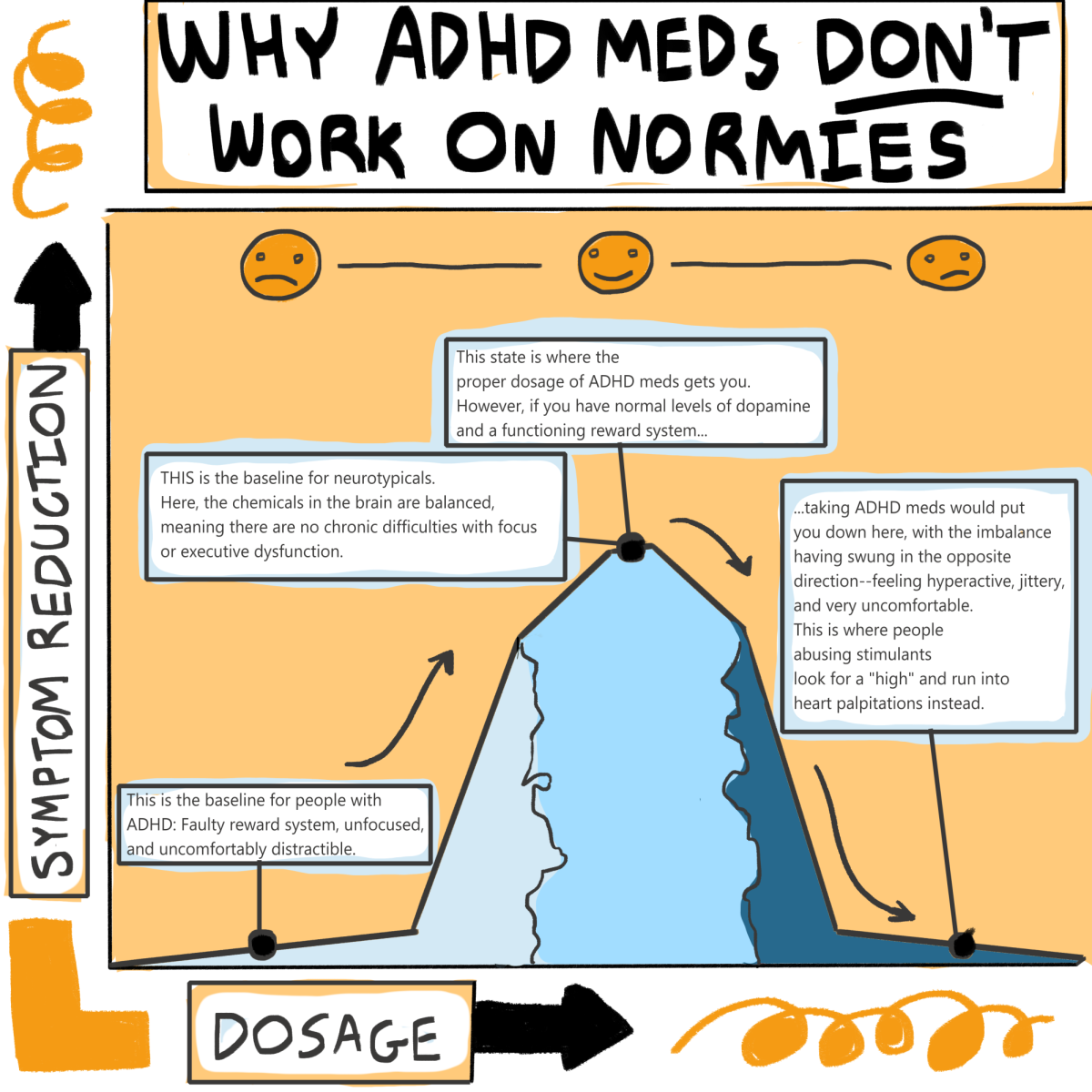

At its core, ADHD is a deficit in the reward system that causes a lack of “happy chemicals,” specifically dopamine and norepinephrine, in the brain. This means that when ADHDers complete a task, their brains are incapable of emotionally rewarding them, no matter how hard they work. The result is executive dysfunction: a constant, oppressive lack of motivation to initiate the most basic endeavors.

While it’s normal to dislike unloading the dishwasher or completing a boring assignment, executive dysfunction is different. No matter how much you want to do something, if your brain decides otherwise, you’re rotting where you sit.

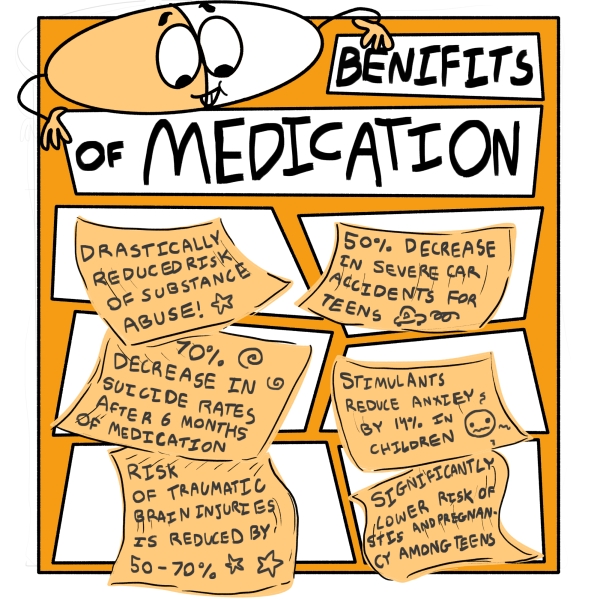

This is where medication comes in. The amphetamine stimulants everyone is so scared of do little more than raise the levels of those brain chemicals to fix the deficit, resulting in a functioning reward system. ADHD meds don’t make people happy constantly, only when they do something worth feeling good about.

Taking the proper dose of a stimulant for the first time can be like wearing glasses after a lifetime of blurred vision, but nobody is against glasses in the classroom. As clear as the world becomes, nothing can magically inform your eyes of the things around you. You still have to read the book and copy the notes. ADHD medication is the same.

When neurotypical people take ADHD meds, they don’t end up with a brain boost. Instead, they get jitters, hyperfocus and the feeling that they’re doing a lot when they actually aren’t. In fact, in nearly every category of cognitive performance, people without ADHD perform worse than they normally would when given amphetamines. Even people with ADHD suffer ill effects if they accidentally take too much. When this happened to sophomore Maddison Cirino, she described feeling “very jittery, extremely uncomfortable and like someone had dumped enough caffeine in [her] to kill a horse.”

When people without ADHD seek out these medications to enhance academic performance, despite research disproving their utility as a study aid, it tends to induce feelings of shame for those who rely on medication to function.

“I have always been told to never tell anyone that I take medication,” senior Georgia Kurland said. “People will come find you, and that’s a very scary thing. You feel like you have to hide who you are, and I think in return, it almost makes you ashamed to get help.”

But people like Kurland don’t have much of a choice. They’re a necessity. “I realized that I wasn’t performing the way that I knew I could. I was studying, I knew the information, but my lack of ability to focus was impairing [my] grades,” Kurland said. “When I did start medication, it changed my life.”

In our current political climate, having ADHD isn’t just disabling, it’s scary. The disorder impacts more than just school; it worms its way into every facet of someone’s life. When people like Kennedy broadcast their “facts” across the internet for all the world to see, I don’t just fear losing medical treatment, but my humanity as well.

While the disorder can never be “cured,” I believe that the world can adapt to our needs, and change starts small. Teachers can ask students about their accommodations and what they can do to help. Friends can stick up for us, offering reassurance and support even if they can’t understand what we go through. Parents can do research, learn the facts and speak to professionals.

“We are at a school where we’re fortunate enough to have kids who have accommodations, [and we have to] remember that it’s not an advantage, and [remember not] to make other students guilty about the things they need to succeed,” Kurland said. “People hear the grades I get and immediately [say], ‘well, you have double time,’ and it feels like a kick down. I think that as a community we have to just understand that people’s brains work differently, and that’s okay.”