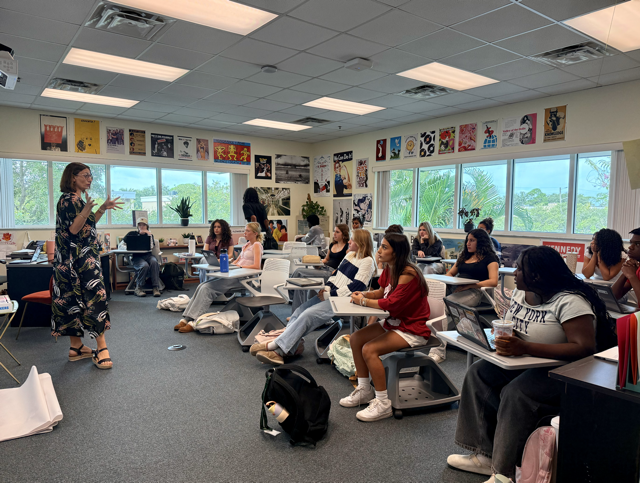

When Board Chairman of the Florida Holocaust Museum Mike Igel spoke to the Shorecrest Upper School, he concluded with the message that the people sitting next to us might have stories as profound as his to share, so we should seek them out. In that spirit, The Chronicle decided to do just that.

On Tuesday, April 2, 2024, Igel presented to the Shorecrest Upper School, in short, about being an upstander. In long, he told the devastating, yet ultimately uplifting, story of his grandparents surviving the Holocaust and the lessons he gleaned from his ancestors.

After hearing from Igel, junior Zev Schulman, whose grandparents are also Holocaust survivors, said he thought the speech “gave [Shorecrest Upper School] a different perspective, probably a more personal story than just hearing about what the Holocaust was, especially hearing directly from a survivor’s descendants. It probably helped people understand more of how brutal and terrible the whole thing was.”

Freshman Diana Muzzarelli is intimately familiar with how brutal it was. Her great-grandfather is also a Holocaust survivor, and she listened to his story growing up.

Before the Holocaust, her great-grandfather was a Polish-German Jew living in a small town in Poland with family nearby, including his cousin Frida and her parents.

The Nazis invaded their small village in Poland when her great-grandfather, Manny Hafler, was about 13 or 14. They “just started shooting. He saw his mother and father and sister shot right in front of his eyes, so all he could do was hide in that moment…He was hiding in the corner of his house or a barn or something, and all he could do was hope.”

Hafler was the only surviving member of his immediate family. However, a little while later, he found out that his cousin Frida and her parents had survived.

Now, without a home, safety, or a community, Hafler and his remaining family had to reckon with their future.

“Eventually they found a farmer who had an attic, it was kind of like a hay loft.” Frida and Hafler’s aunt and uncle asked the farmer to stay, and he agreed, but only for the three of them, since Hafler joined the trio later and snuck into the attic.

Hafler’s uncle originally didn’t let him into the loft, but his aunt insisted. Hafler had almost been abandoned.

“In the hayloft, it was very shallow and they couldn’t stand up, and kind of all they could do was lie there. The farm was right next to the Gestapo (the Nazi secret police) so they couldn’t talk. If they talked, they would get shot. So they went two years without talking, standing up—just lying there.”

The farmer sent up a pail with bread, potatoes, and water daily, but “only enough food for three people because he thought there were three people there. And my great-grandpa’s at the most formative stages of his life—13, 14, 15—I don’t think he got out until he was 17, so he was always hungry, and there wasn’t enough food for everyone. So, Frida and her mom shared with him, but it wasn’t even close to enough.”

After being liberated, Hafler couldn’t walk since he had been lying down for years without end. He was rushed to a hospital where he was abandoned by Frida and her parents.

Cont:

“There were camps to try to get people whose parents were killed back on their feet. So he went into one of those camps for a while and in this camp he learned how to walk again.” At the age of 17, Hafler was learning to walk again. He had to restart his life, beginning with the opportunity to go to America.

Igel and Muzzarelli’s stories, while vastly different, have underlying similarities in their messages.

Igel’s story was about how “everybody’s lives are kind of dependent on each other, just because of how he was always emphasizing that he wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for the heroic actions of some other people saving his grandparents. Everything leads to one another, and something that might seem small in the past has massive implications in the future,” said Schulman.

Both stories emphasize how, without the compassion of strangers, entire familial lines would’ve been gone. In Muzzarelli’s story, without the farmer providing shelter and food, Hafler, Frida, and her parents wouldn’t have survived.

For Muzzarelli, she took away that “in a time of so much hate, [the upstanders] could find a way to give love and give it back to the community. They genuinely did every single thing they could for [my grandfather’s] family, and I think that’s really incredible…The farmer risked his life for my family, and unfortunately we don’t really know anything about who he is.”

Schulman, in a similar vein, said, “The people were the true heroes of that time. He mentioned upstanders and bystanders, so maybe he was trying to connect that to what you do within your life and whether you’re going to be an upstander or a bystander and take control when you’re an adult and need to do the right thing.”

And that was Igel’s message, that these stories full of so much tragedy can not only shed light on historical events, but can make impressions upon the listeners of these stories and help them be better versions of themselves.

![Thespians pose on a staircase at the District IV Thespian Festival. [Front to back] Luca Baker, Maddison Cirino, Tanyiah Ellison, Alex Lewis, Summer Farkas, Jill Marcus, Ella Mathews, Sanjay Sinha, Isabella Jank, Sofia Lee, Boston Littlepage-Santana, Sally Keane, Tyler Biggar, Tanner Johnson, Jasper Hallock-Wishner, Remy de Paris, Alex Jank, Kaelie Dieter, and Daniel Cooper. Photo by Michael McCarthy.](https://spschronicle.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/image1-900x1200.jpg)