In December of 2024, The Chronicle published an editorial criticizing the culture of academic competition at Shorecrest. The piece acknowledges a real problem, and like all problems, there’s a cause–though not one rooted in unkindness. In fact, no one at Shorecrest is at fault.

As a private preparatory school in the Tampa Bay area, Shorecrest is expected to offer AP classes–and it does, with over 20 for students to choose from. This is partly due to the fact that an AP is considered to be the most impressive class by many non-educators: your child gets to take a college-level course, sometimes gain college credit, and it’s seamlessly integrated into their high school record.

No wonder they’re so popular. Shorecrest isn’t the only school who’s feeling the love: According to College Board, 80 percent of public schools offer AP courses, and while that statistic is estimated to be lower for private institutions, in Florida, their presence is widespread.

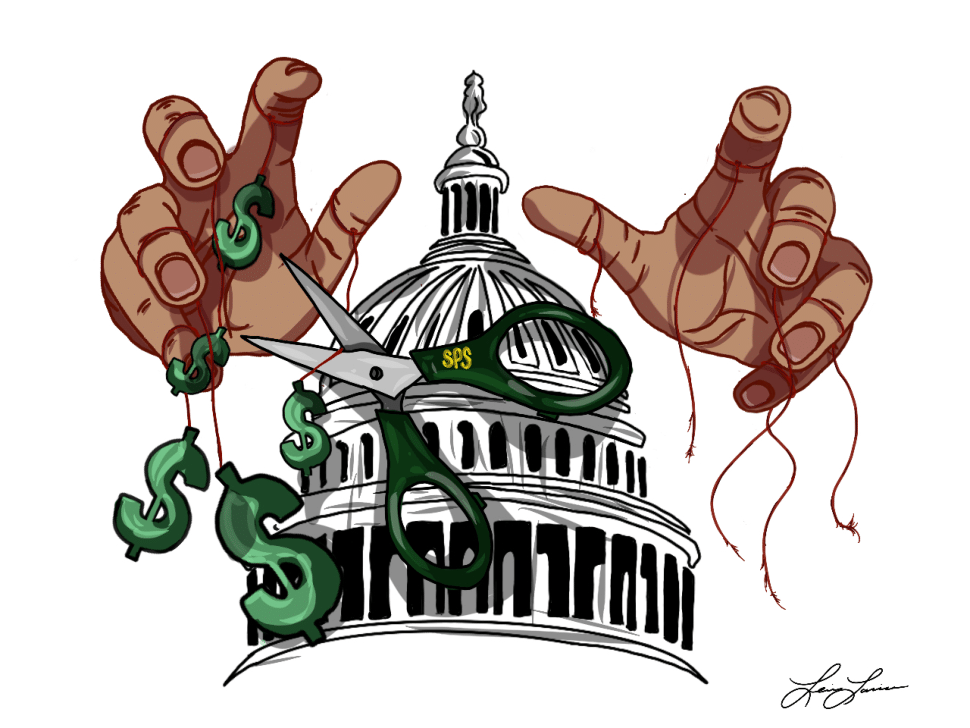

But the power that College Board has over millions of American students is problematic. Despite what their website would have you think, few benefit from this “not for profit” kingdom–except, of course, the CEO, who makes just over two million dollars annually.

In short, College Board is a parasite on the United States educational system.

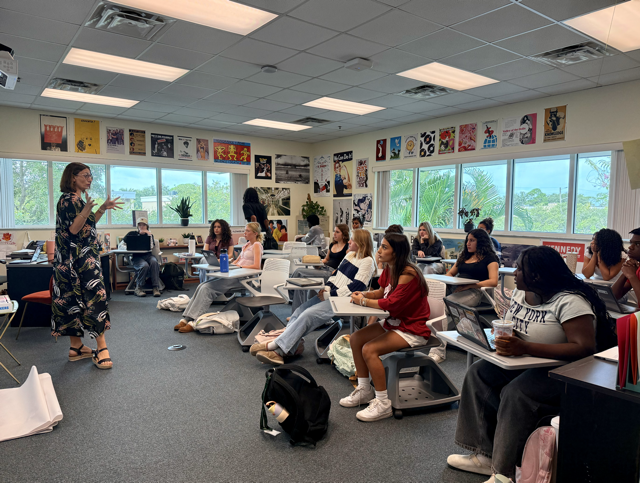

US Visual Arts Department Chair Charla Gaglio likens the company to an art critic: “They come in and say, this art is good, and you should invest in it. And then the art buyers who don’t have the background will listen to that and [miss out] on some really good artists,” she said. “I think the College Board does the same thing…It’s a fabricated entity that has inserted itself between the actual consumer of the product, the student, and the actual product, which is the university.”

And there’s no real alternative to AP courses. They function as an easy way for colleges–especially larger ones–to assess the merit of a student’s application: a number can tell admissions officers all they need to know. It’s cheaper for the academic institutions, who don’t have to pay for the hours it would otherwise take to more thoroughly assess thousands of transcripts.

The problem is, a test grade can never encapsulate the rich inner life of a teenager. As Gaglio put it, “Human beings are not numbered products.”

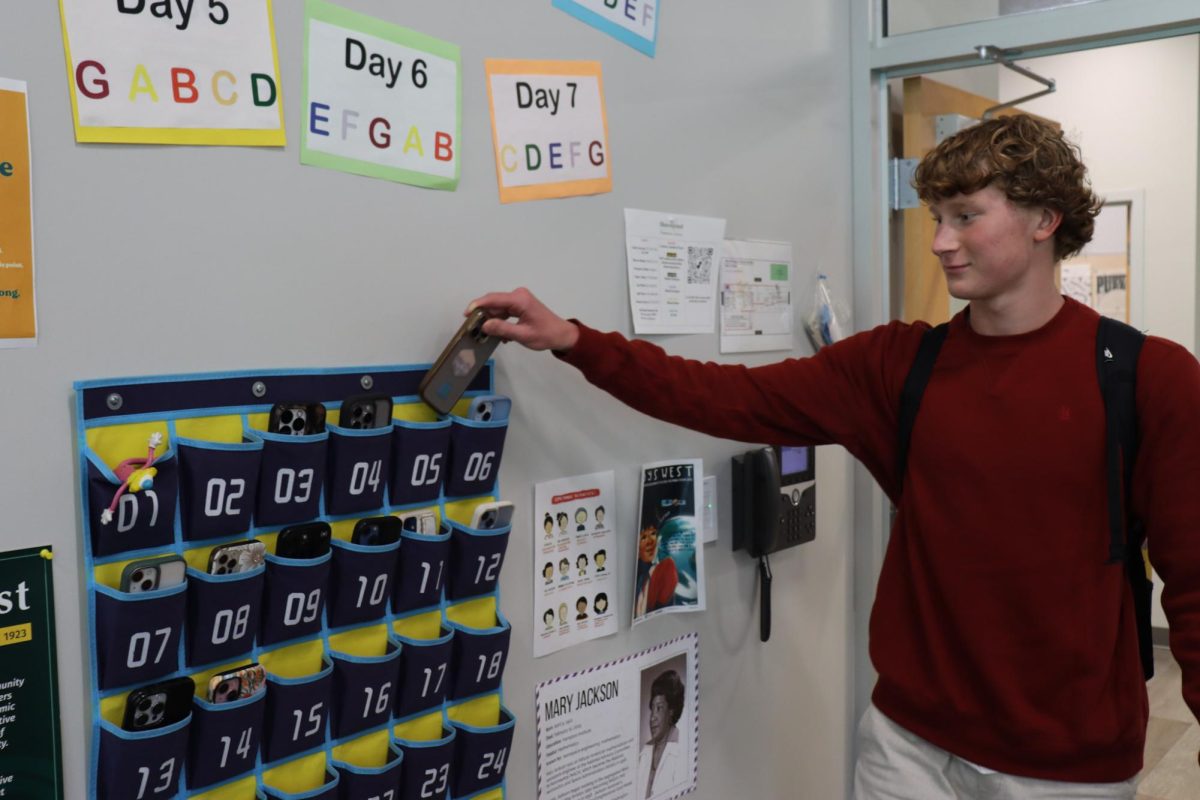

When APs are the most important factor on an academic record, demand among students is high–but the exams come with a hefty price. At $99 per test, College Board has introduced yet another pay-to-play element to the American college admissions process–and that’s not to mention SATs, which cost around $70 to take digitally.

This puts Shorecrest in quite the bind. The school’s goal is to get students to college, especially Florida universities–that’s the path that parents, kids, and admissions officers follow. If APs are a necessary part of that process, their presence is inevitable.

At the same time, Shorecrest is in active competition with numerous nearby private and public high schools, who all offer AP courses. Why? Because if they didn’t offer APs, they would lose their clients. Simply put, if those classes are the highest standard, Shorecrest has no choice but to push them. Hard.

Assistant Director of College Counseling Victoria Scott acknowledged the current reliance on numbers to define students. “APs [are], in this context, the path for students to get to where they need to get, data-wise, to be ready for a selective university…Once the students and families see that, that’s going to then drive everything they do, because even if they want to be outside, investigating leaves and learning biology through a different lens, that’s not the game we play.” She said. “It’s a rat race.”

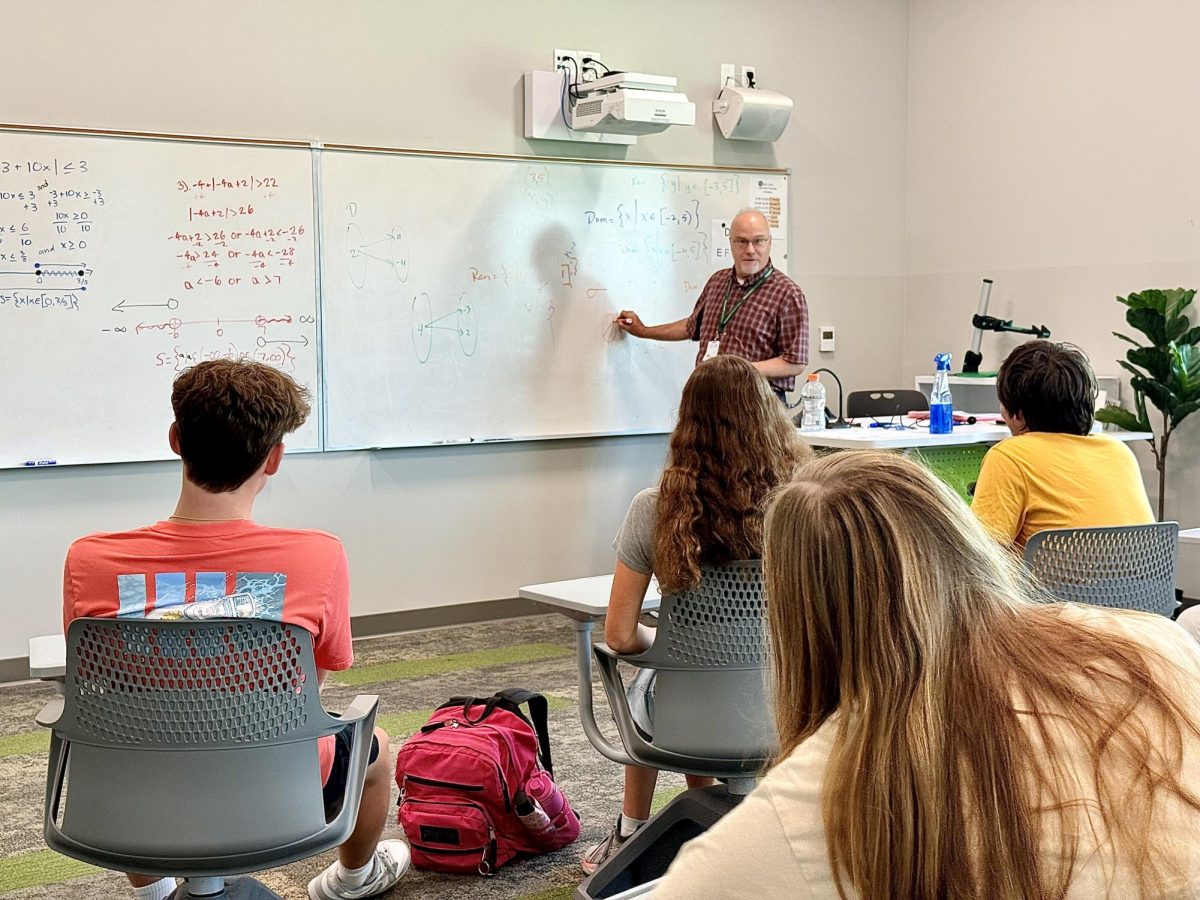

That isn’t to say that AP courses are lacking quality. US Social Studies Department Chair & GSI Director Kayla Brazee affirms their value. “I really appreciate teaching the skills needed to do well in an AP class,” she said. “[They] require the students to take a more active role in their learning, and I think [that] is a positive.”

The English courses especially allow teachers freedom in the classroom. They get to choose which books to teach, and while they have to prepare students for an exam, the pressure isn’t oppressive. But when the end goal of any class is a certain grade, that number becomes the incentive, not the knowledge you could gain.

“I do feel like AP classes stifle the natural curiosity of students,” said Brazee. “I’ve had students [ask] me, ‘is this going to be on the test?’ Which makes me go, ‘oh, right, okay–maybe we’re not necessarily interested in learning interesting things.’”

This issue with AP courses–and really, College Board’s monopoly as a whole–is only a symptom of the nationwide grade-emphasis placed on high school students everywhere. Even at private institutions that don’t offer APs, like the Hotchkiss School in Connecticut, academic rigor is overwhelming for students. School goes six days a week, and classes assign hours of homework nightly.

Mental and physical health often end up neglected in favor of work. While APs draw criticism for their rigid curriculums, the stress that students experience taking high-level courses of any kind is universal in preparatory institutions within the United States, regardless of how their school is structured.

If Shorecrest were to stop offering APs–instead pursuing more enriching, fun, experience-based classes–parents would likely take their business elsewhere, and college competitiveness would drop. In this environment–one that College Board perpetuates–grades, inevitably, can’t just be grades: they’re your future, your measure of intelligence, your value as a person. Students, at the end of it, can’t be learning for the sake of learning. And that, quite frankly, sucks.

Presently, there’s no solution to this problem. For the time being, Shorecrest needs to keep APs in the spotlight in order to thrive. This means classes focused on exploration and creativity, where teachers can wholly dedicate themselves to what fascinates them and their students, are limited in both supply and demand.

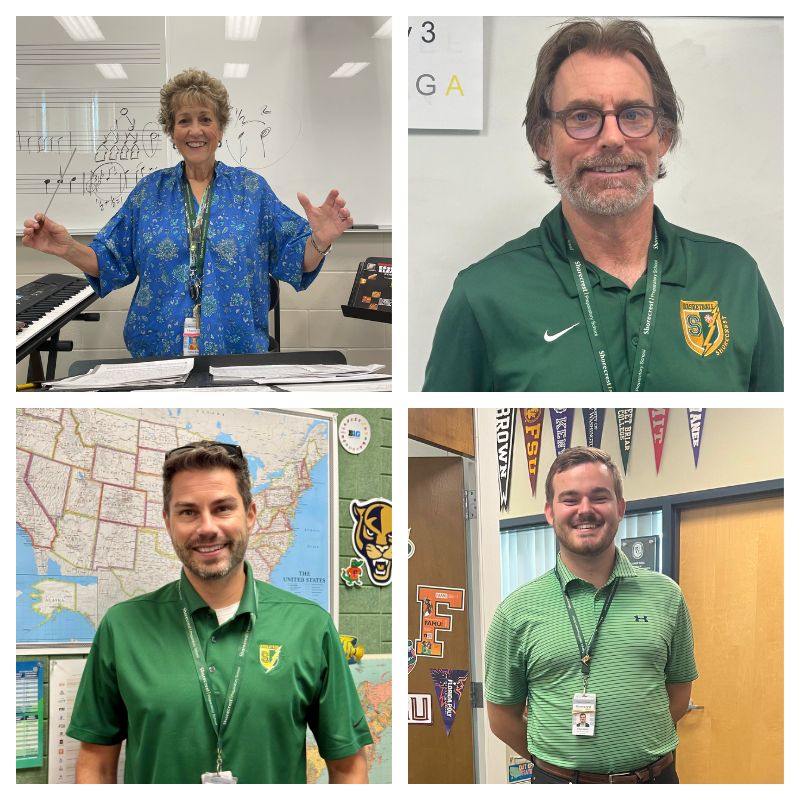

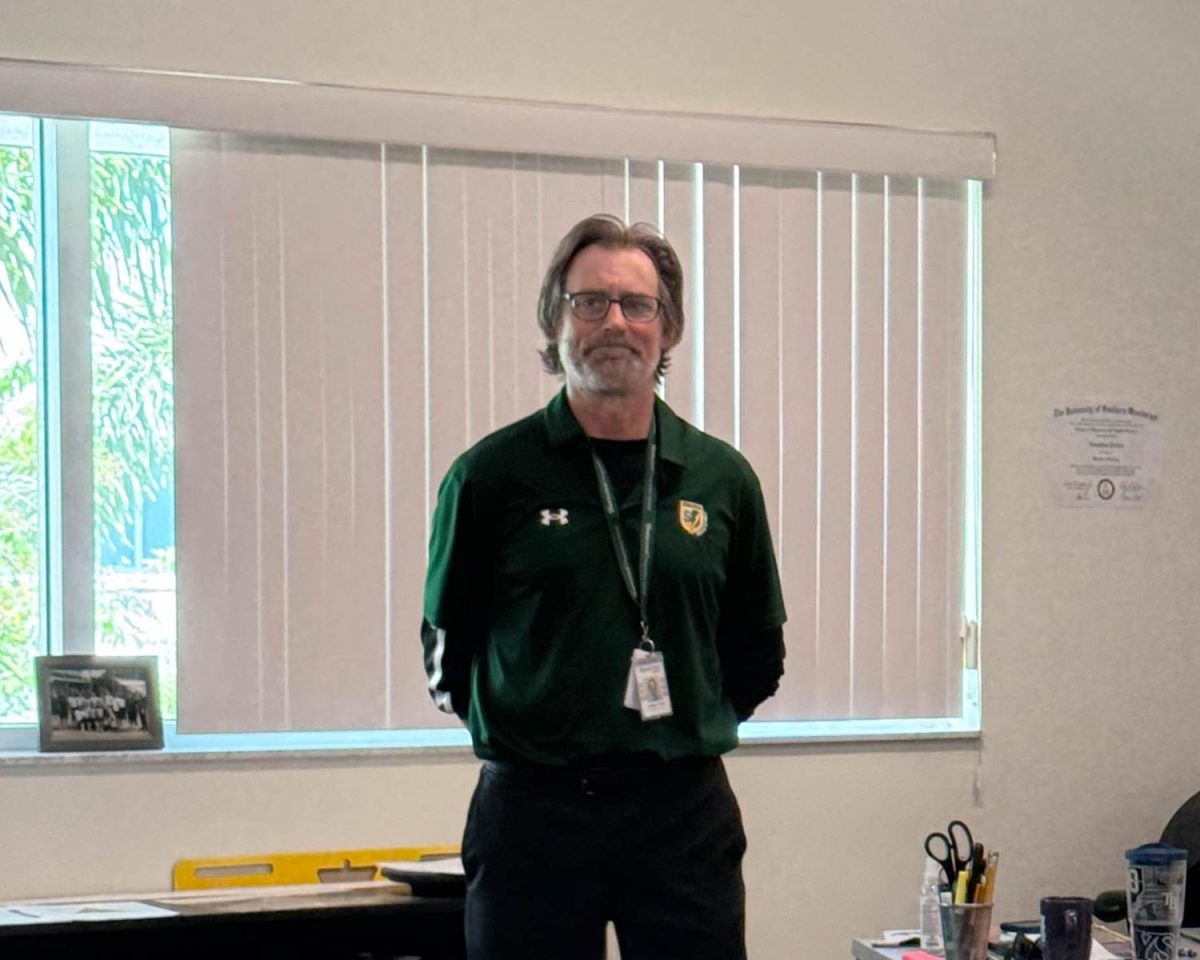

As top colleges become more and more selective, high school students are forced to push harder and harder to achieve the bare minimum the world requires of them. In turn, this further fosters the atmosphere of stress and competition rampant within the walls of the school. Admin and faculty can’t change it–it’s entirely beyond their control. All they can do is foster kindness and support whenever possible, and do what they do best: teach, despite the challenges.

Fortunately for Shorecrest, their educators aren’t ones to back down. “I think sometimes the biggest divide between the adults in this school and the students [is that] the students think the adults don’t understand,” said Scott. “[We] understand more than [the students] could possibly understand, but we play a game that we can’t change, and so we come to work every day being the most optimistic we can within a system we did not create…The adults on campus care so much, and they hear all of you.”

![Thespians pose on a staircase at the District IV Thespian Festival. [Front to back] Luca Baker, Maddison Cirino, Tanyiah Ellison, Alex Lewis, Summer Farkas, Jill Marcus, Ella Mathews, Sanjay Sinha, Isabella Jank, Sofia Lee, Boston Littlepage-Santana, Sally Keane, Tyler Biggar, Tanner Johnson, Jasper Hallock-Wishner, Remy de Paris, Alex Jank, Kaelie Dieter, and Daniel Cooper. Photo by Michael McCarthy.](https://spschronicle.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/image1-900x1200.jpg)