Before 2019, hearing “sksksk” was odd, and, in some cases, alarming. However, with the rise of VSCO in 2020, brightly colored scrunchies, “sksksk,” and reusable water bottle trends became rather common. VSCO teens were notorious for their Hydro Flasks—the bottles practically glued to their hands.

Society today continues to be influenced by water bottle culture. Most recently, a craze over a gargantuan 40-ounce monster—the Stanley Quencher H2.0 FlowState Tumbler—captured the gaze of many. Stanley users, like those before them, believe they are being eco-conscious by substituting single-use plastic with “sustainable” materials, but environmental benefits are minimized when reusable bottles are treated as an accessory rather than a utility.

Stanleys and most other insulated bottles are composed of stainless steel, an alloy that requires large amounts of energy and natural resources to create, and even more energy to process, leading to pollution and carbon dioxide emissions.

Despite stainless steel being a recyclable compound, Stanleys are practically destined for an afterlife in a landfill due to the polymer-based powder coating their exterior that creates the perfect violet or bubblegum hue. According to Plastic Education, because of the high environmental cost of these bottles, scientists estimate that it would take roughly 30-90 uses to match the environmental impacts of single-use water bottles.

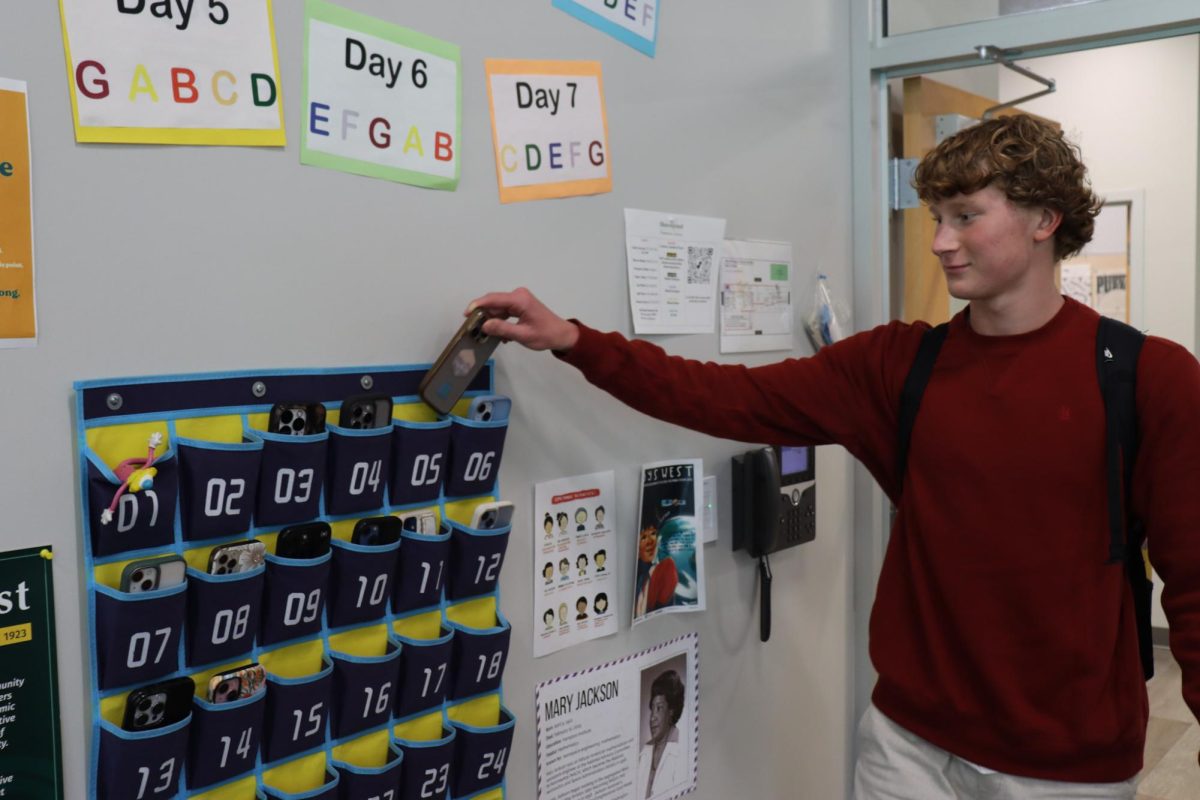

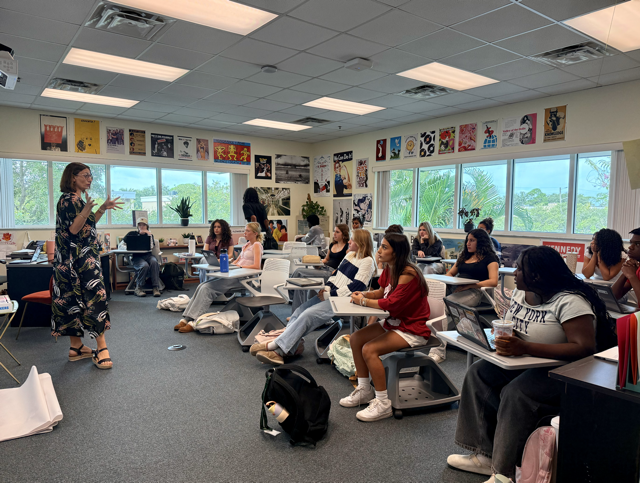

According to US Administrative Assistant Fatima Morlando, “In the more recent years, there has been an influx of fancy water bottles that everybody has to change when the new trend comes out, so in the last few years, it’s [the number of bottles in the ‘lost and found’] been more.”

Upper School Dean of Student Life Stacy Alexander, whose Yeti water bottle has been her steady companion for six years and counting, said, “I do applaud our kids for using reusable water bottles… But when you lose your water bottles, then that’s just adding to the landfill.”

So while one Stanley purchase may not be detrimental to the environment, it’s the cycle of purchasing one bottle, losing it, and then repurchasing it that perpetuates the pollution.

Morlando mentioned a recent event regarding a student’s reunion with his long-lost thermoses. As she was getting rid of some bottles “he [the student in question] started looking down and realizing that 7 of those water bottles were his.” Morlando said that most of the bottles were “fancy” as well. As for the many bottles that never find their owners, a lifetime of slow, tedious, and partial decomposition awaits.

Alas, one might not need to sacrifice their Stanleys entirely. For aspiring environmentalists with Stanley addictions, Middle School Marine Science Teacher Kathryn Jeakle suggests a solution. “What would be cool,” said Jeakle, “is if we had some campaign where we collected [reusable bottles]…washed them well, and donated them.”

![Thespians pose on a staircase at the District IV Thespian Festival. [Front to back] Luca Baker, Maddison Cirino, Tanyiah Ellison, Alex Lewis, Summer Farkas, Jill Marcus, Ella Mathews, Sanjay Sinha, Isabella Jank, Sofia Lee, Boston Littlepage-Santana, Sally Keane, Tyler Biggar, Tanner Johnson, Jasper Hallock-Wishner, Remy de Paris, Alex Jank, Kaelie Dieter, and Daniel Cooper. Photo by Michael McCarthy.](https://spschronicle.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/image1-900x1200.jpg)