Everyone loves a good murder story, but US Learning Specialist Jennifer Hart lived it.

Living in Gainesville during the Gainesville Murders in 1990 — when five college students were murdered in their apartments — Hart’s freshman year of college was focused more on who the next victim would be, rather than her studies. While true crime was Hart’s morbid reality, today it’s others’ morbid entertainment.

Thanks to Spotify, Apple and other streaming services, our true crime queries can be answered. Now, your favorite murder stories, sparing no bloody details, are at your fingerprints. Pick your poison: “My Favorite Murder” or “Serial.”

What Is True Crime Media?

True crime — the media’s favorite child — is the exploration of real-life criminal events, told through podcasts, movies, TV shows, social media and books. The majority of the content emphasizes morbidity, primarily describing murders and kidnappings.

“I like the documentaries on Netflix that are about homicide or criminal cases,” aspiring criminologist and true-crime enthusiast junior Riley McClung said. “I watch a lot of short YouTube videos, and I would say a lot of the interviewers and detective people really have a strong mind behind knowing when someone’s lying.”

But some might say the focus of true crime has shifted from telling the real story to telling the “best” story, trying to lure the most viewers with a focus on blood, gore and mind tricks.

The Gainesville Murders

The media can often convince people that serial killers and murder are something that will never come near them. However, Dr. Hart was a witness to the Gainesville Murders in 1990.

Barely a month into her freshman year at Santa Fe College, Dr. Hart awoke to a call from her mother to see if she and her sister were okay.

“That was just the beginning of the whirlwind,” she said.

Two sisters — the same age as Dr. Hart and her sister — were reported murdered that morning.

“Their apartment was probably a mile away from mine. That’s not far.”

These murders only continued. That night, two more people were reported murdered, and Dr. Hart’s mother urged her to come home, but she refused.

“Being eighteen, I knew more than my parents,” she said.

The city was covered in police and people were frightened.

“So many friends and families were worried about us. My mom was terrified.”

Hardly any information was being shared about the murders with the public at this point, and Dr. Hart was living in an apartment block with lots of male neighbors, so she felt somewhat protected.

In total, five were reported dead, and Dr. Hart later found out that she lived only two miles away from the killer.

“He was living in the woods just off the main roads in a tent [which] went down a deep, dark hole,” Hart said.

What Dr. Hart learned from this experience is that true crime doesn’t have to be accurate reporting to be ethical reporting.

“There were some gruesome details about something done to one of the bodies, and I won’t say what it was, but it was so horrific that one of the first responding police officers ended up committing suicide because it just disturbed him so much,” Dr. Hart said. “That kind of information didn’t come out into the public out of respect for their families. It’s really one of those things where you know the public didn’t need to know that detail.”

Popularity

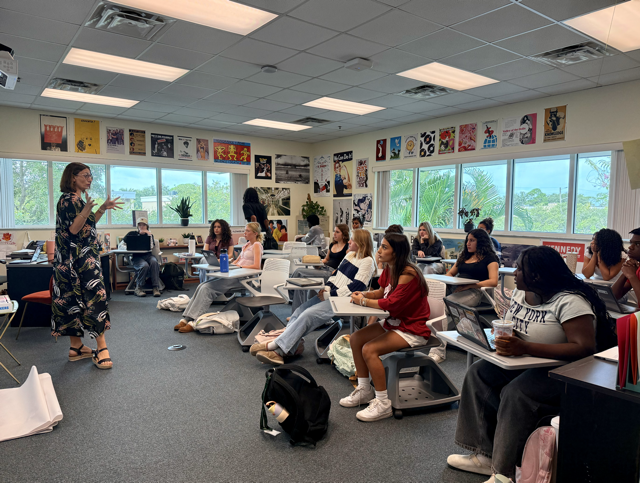

Shorecrest’s AP English Language & Composition classes read Truman Capote’s “In Cold Blood” every year — the book that started it all. With the journalistic telling of the Clutter family murders, this nonfiction story was the first true-crime novel to be published.

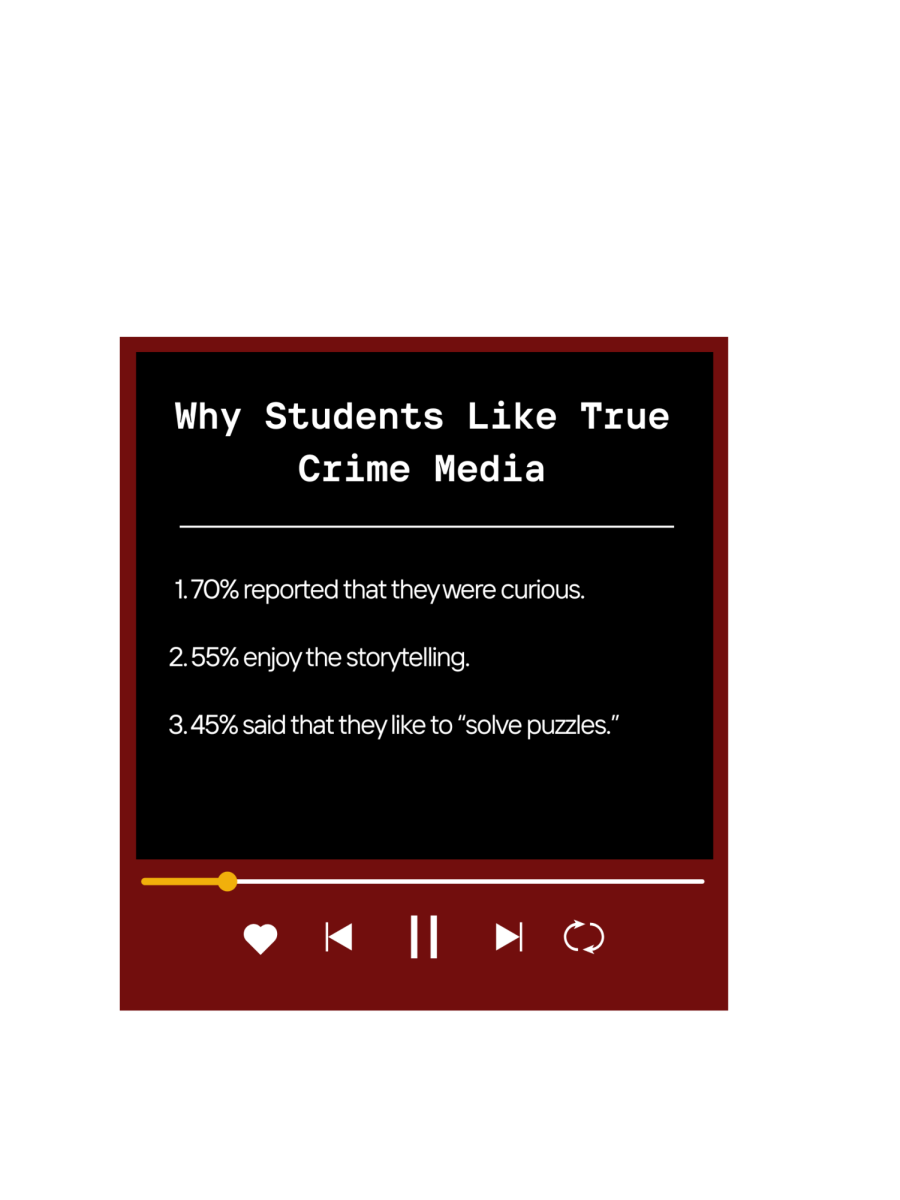

Ever since then, true crime has become more and more popular. In a survey of 117 students, 39.3 percent reported that they consume true-crime media regularly.

“I think I like it because you get the thrill and the mystery. You get to figure out how it all leads up to one thing,” McClung said.

As popular as true crime is, it tends to be consumed more often by a specific demographic. According to a 2023 article by the Pew Research Center, U.S. female podcast listeners are almost twice as likely to listen to the true-crime genre as male podcast listeners.

“I wonder if women watch because they have a higher level of empathy,” true crime watcher and US English Teacher and 10th Grade Dean Heather Elouej said. “Maybe women watch as a way to — even if they’re not aware that they’re doing so — prepare for surviving violent attacks. When we consider the devastating statistics concerning murder, domestic abuse, child abuse and sexual violence, I believe more people, not just women, have been touched by true crime than not.”

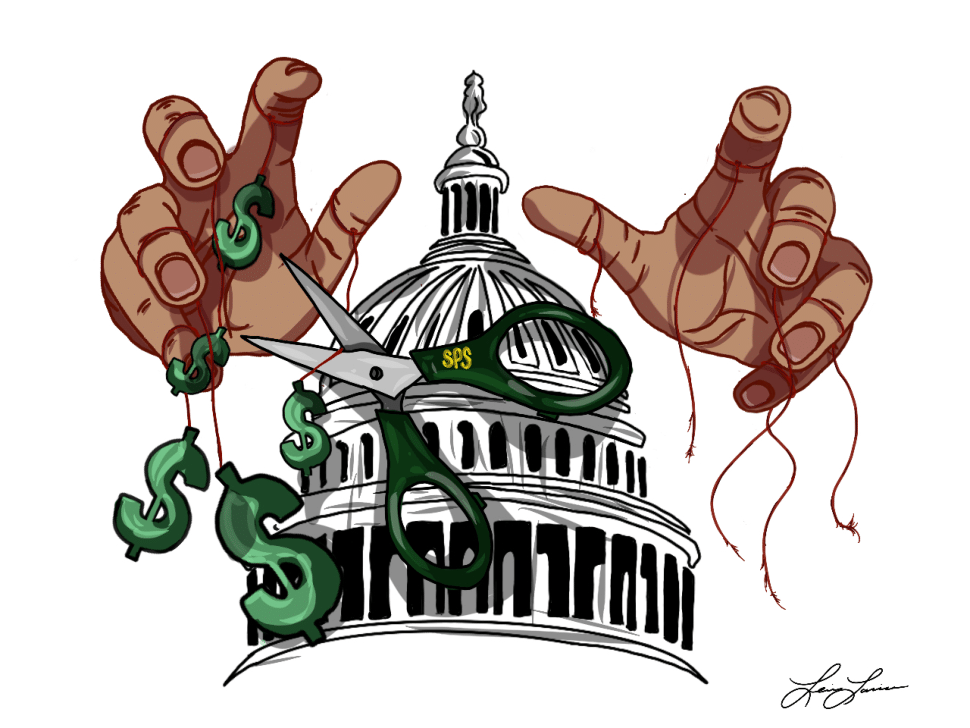

The Ethical Dilemma Behind True Crime

However, there is a lot of controversy surrounding true crime, as numerous podcasts fail to get consent from victims’ families. Channels like “Cookies and Crime” make videos decorating cookies or doing makeup while discussing murders, which many see as insensitive.

“I imagine some [true-crime media] portray things a lot more realistically than others. Some, I feel, just want to grab the viewer’s attention and get a good story out there. I imagine others are trying to actually figure out what’s going on. But, unless you’re the people who are working on the case, it’s very hard to get that type of information,” junior and co-president of the Forensics Club, Indi Wells said.

But with every entertainment source comes a market, and profiting off of people’s misfortunes with advertisements or merchandise are just some of the examples of how true crime can be turned into a business. You can get a Ted Bundy shirt for just $19.95, for example.

But this is no joke. Murder and kidnappings happen to real people daily. Podcasts like “My Favorite Murder” seem not to care. Their slogan, “stay sexy and don’t get murdered,” is one of the many things on the podcast with a “comedic” twist.

And social media isn’t off the hook. Memes, TikToks and videos mock these traumas, which can come across as unsympathetic.

After the release of Netflix’s “Dahmer” — a series about the infamous cannibal, Jeffrey Dahmer — memes spread across TikTok faster than you could dial 911. These included “unfazed” reaction videos and fan edits, because nothing says hot like a cold-blooded killer.

“If true crime program creators don’t make efforts to humanize victims, I worry that consumers of true-crime media will become desensitized, that they will blur the line between entertainment and the horrors exacted on real victims and their real families in the aftermath,” Elouej said.

However, the concept of true crime isn’t the thing people typically disagree with, but the fact that many often see it handled so indelicately.

“I think just reporting on an event that happened in the past, like a murder, is not wrong. It’s the same thing as any journalist would do. You report the facts, you say what happened and you keep people informed of the horrors so that people can be warned for the future and remain alert,” senior and true-crime consumer Emma Moya said. “At the same time, I have heard of some incidents where whoever’s reporting on the true crime passes the boundaries of invading privacy. You’re revealing private names or private addresses just for the sake of providing all the facts. And I do think that crosses a boundary of actually hurting the people that were left alive or the people that are grieving.”

Mental Health Effects

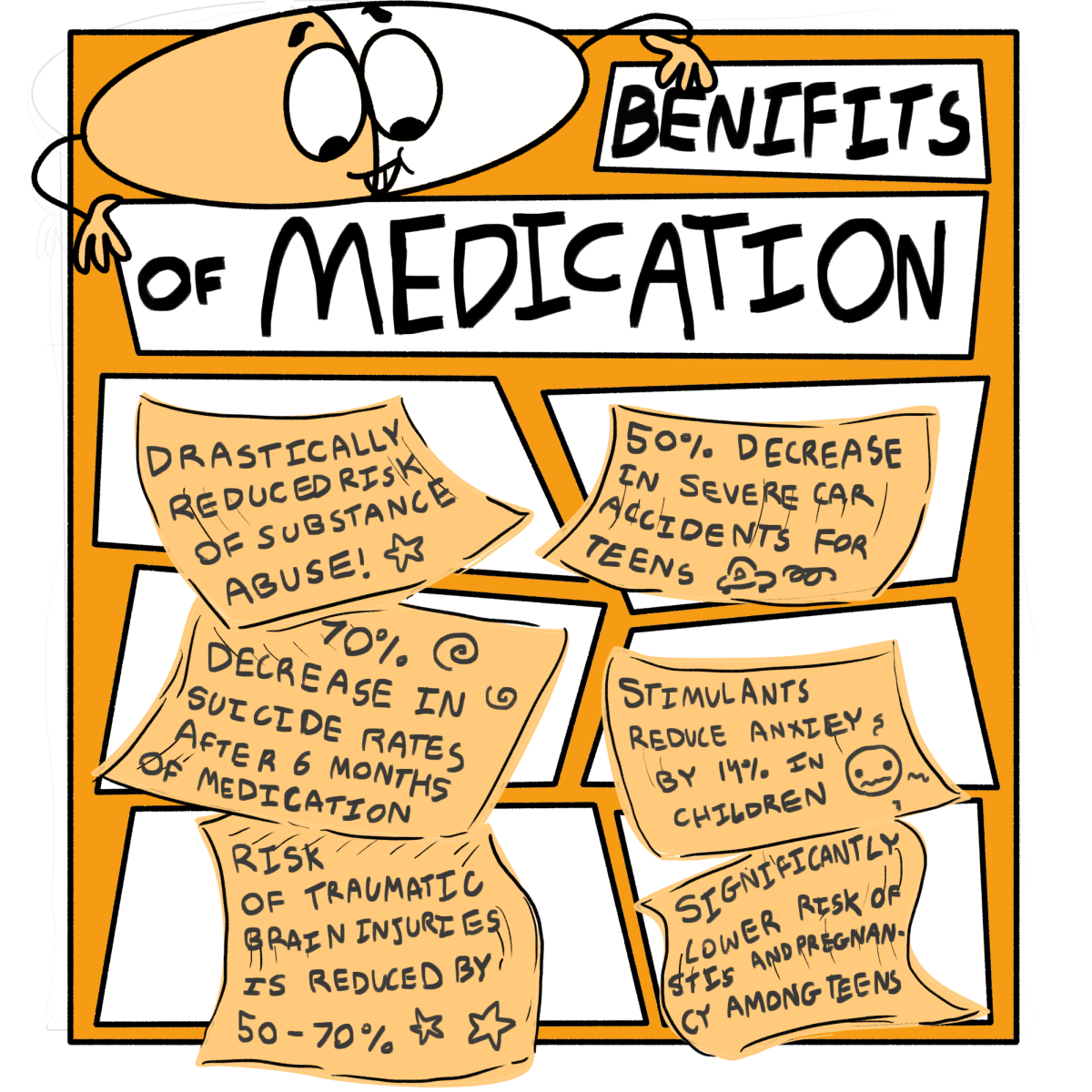

Getting goosebumps after hearing about the brutal murder of a young woman isn’t uncommon. According to Better Help, consuming true-crime media can lead to an increase in anxiety, panic attacks, obsessive thoughts, troubled sleep, paranoia and retraumatization.

After the Gainesville Murders, Hart became obsessed with a series of true crime books, but had to put her mental health first and put the books down, as she became paranoid and obsessed.

Wells said, “Whenever I go on road trips, my mom will always play true crime, and my dad is like, ‘Can we just turn that off?’ It actually makes him anxious and stressed out.”

It’s not just unwilling participants who get the heebie jeebies, but also many true-crime fans themselves, even if it’s not permanent.

“In the moment, maybe you feel the chill of, ‘Oh my God, this could actually happen.’ But I’ve never been one to really internalize it. I feel like I’ve always been pretty conscious that this could happen, but at the same time, so could World War III, and we’re still here,” Moya said.

Case Closed

When listening to your favorite murder podcast or watching a true-crime show, it’s important to think about how it affects American culture — not just the killer’s “lethal” face card.

As the sirens sound and police are swarming your house, maybe a 22-year-old makeup artist is talking about your loved one’s death. Maybe someone is voicing over your murder, with caution tape and blood splattering on every American’s TV screen.

“If that were my kid, I would say, I don’t want certain things put out in the media, because it’s just too much,” Dr. Hart said. “It’s too personal, and it shouldn’t be anybody else’s business, other than those who are involved in the case.”

![Thespians pose on a staircase at the District IV Thespian Festival. [Front to back] Luca Baker, Maddison Cirino, Tanyiah Ellison, Alex Lewis, Summer Farkas, Jill Marcus, Ella Mathews, Sanjay Sinha, Isabella Jank, Sofia Lee, Boston Littlepage-Santana, Sally Keane, Tyler Biggar, Tanner Johnson, Jasper Hallock-Wishner, Remy de Paris, Alex Jank, Kaelie Dieter, and Daniel Cooper. Photo by Michael McCarthy.](https://spschronicle.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/image1-900x1200.jpg)